The nurturing of virtuous qualities has been a common endeavour of various philosophical and contemplative traditions (Eifring, 2015; Gethin, 1998). Constructive meditation practices were one of the methods developed and used by these traditions to foster the cultivation of a virtuous ethic. As with attentional meditation practices, constructive practices, need meta-awareness but they also serve to strengthen and sustain meta-awareness (Dahl, Lutz, & Davidson, 2015). Although constructive practices take a whole different approach to attentional practices. In what way you might ask?

Constructive meditation practices

As opposed to attentional practices, which take an approach of noting and observing the rising and falling of our emotions, thoughts and perceptions. In constructive meditation practices, you take an active role in trying to “change” the cognitive and emotional content of your experience. Mostly this is done by extending loving-kindness and compassion towards oneself and others (Gilbert & Choden, 2014).

By taking a more active approach at addressing our thoughts and emotions. Dahl, et al. (Dahl, Lutz, & Davidson, 2015) argue that constructive practices might effect your wellbeing by trying to replace maladaptive self-schemas with more adaptive ones. This in contrast to attentional practices which look at observing the contents of our experiences.

Not excluding that there are diverse forms of constructive meditation practices. With each having its own unique design. For example, some constructive practices try to cultivate patience and equanimity (Gethin, 1998). While others take a reorienting approach towards our values and priorities in life (Mingyur & Tworkov, 2014). Still, other constructive practices focus on our interpersonal relationship by trying to nurture qualities of kindness and compassion (Gilbert & Choden, 2014).

Those that focus on our interpersonal relationship by trying to nurture qualities of kindness and compassion are the main group and in this article, we will focus on them.

Cognitive processes: Cognitive reappraisal and perspective taking

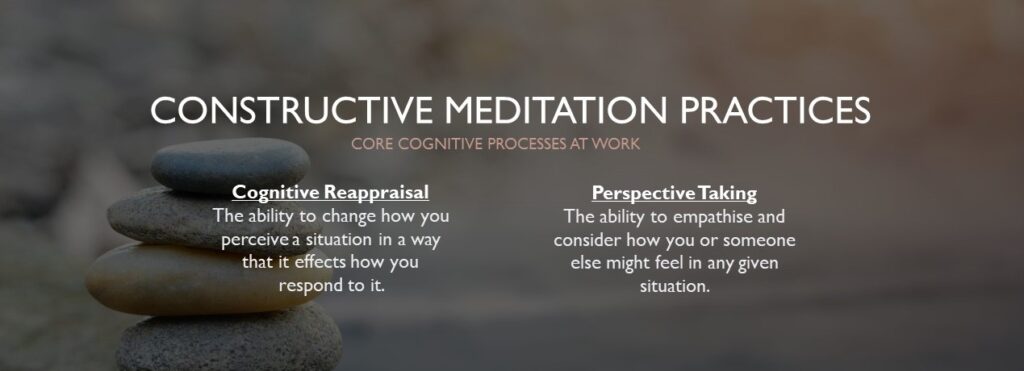

Unlike attentional meditation practices, you might think that the variety of constructive meditation practices might make identifying the particular cognitive processes at work difficult. Nevertheless, Dahl, et al. (2015) argue that if you take a closer look at what is in common between the different constructive meditation practices. You might notice that there seem to be two core processes at work:

- Cognitive reappraisal: having the ability to change how you perceive a situation in a way that it effects how you respond to it.

- Perspective taking: Or simply the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Coupled with the ability to consider how you or someone else might feel in any given situation.

Cognitive reappraisal

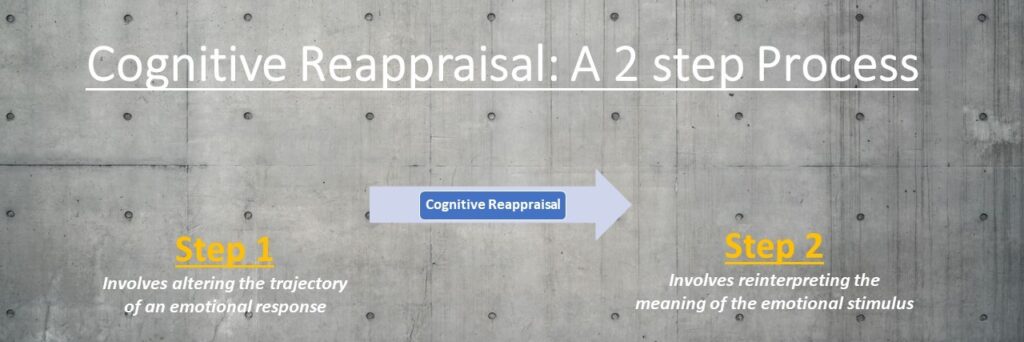

The first core cognitive process at work, reappraisal, is actually an emotional regulation strategy where you take an active two-step role (Webb, Miles, & Sheeran, 2012).

The first step involves altering the trajectory of an emotional response. Here we can see the link between attentional and constructive meditation practices, and how constructive practices build on the cognitive processes of emotional regulation cultivated in attentional meditation practices. Why? Because you need to be able to regulate your emotions to change their trajectory.

The second step involves reinterpreting the meaning of the emotional stimulus. Here again, we can see the link between attentional and constructive meditation practice. As this step would require a kind of distancing from what you are feeling. Or a space between you and what you are feeling, not to be fused with what you are experiencing. And as we saw in part 1 of this 3-part series attentional meditation practices actually counter cognitive fusion.

An example: Cognitive reappraisal at work

Let us say that due to circumstances you might do badly in a series of tests. Initially, you might go into a negative spree about your performance. What an utter failure you are and that you should quit the course.

later you might try grounding yourself and revisit your initial emotional response to the situation. On doing this you might realise that lately, you were going through a lot (example: the death of a family member, losing your job, struggling financially). And you might realise that it is not because you are a failure that you got bad results. But because you might have been stressed as a consequence of some life-changing situation.

This might change the way you view the results. For example, you might realise that all in all when compared to your usual performance. You might have not done that badly considering what you were going through and you still passed and made it through to your next year. Looking closer you might also realise that you did not perform below the class average. This might be compared to step one – the recognition of one’s negative response.

Then you might notice that considering you lost your job doing the course might actually be a blessing. Not only as all in all, with all that you were going through you demonstrated a lot of resourcefulness in dealing with everything and congratulate yourself for your resilience.

Realising that you have the resilience to rise up to challenges and that next year might be an opportunity to rise up above these challenges. This might be considered as step 2 reinterpretation of the situation to either reduce the severity of the negative response or exchange the negative attitude for a more positive attitude.

Appraisal-focused coping

This strategy is called appraisal-focused coping (Taylor, 2017). One of the three broad categories of coping which also include problem-focused coping, and emotion-focused coping. It differs from the other two methods of coping because it primarily addresses an individual’s perception of a situation, rather than directly altering environmental stressors or emotional responses to those stressors. (If you wish me to make a blog post on these coping styles and how they differ from each other leave a comment below).

Perspective taking

The second core process perspective-taking is the act of considering how oneself or another would feel in a particular situation (Lamm, Batson, & Decety, 2007). This is related to your ability to empathize and perceive what someone else’s thoughts feelings and motivations are.

Perspective taking goes a step further than empathy as it requires you to put yourself in the other person’s position and imagine what you would feel, think, or do if you were in that situation. This can help you better understand someone else’s actions.

3 core skills of Perspective taking

Perspective-taking involves several distinct skills (Galinsky, 2010), with the following being the core skills:

- Determining how someone else feels. use our knowledge and understanding of past experiences

to try to understand how someone might feel. The challenge here is that while we are doing

so we must also ignore our own opinions, thoughts or feelings. This takes us to the next skill. - Inhibitory control. To be able to perceive the world as

someone else would see it. To do this we

have to put our own thoughts and how we feel about a situation on hold. This is an emotional regulation skill. Here we again see the connection between attentional

and constructive meditation practices and how they build onto the cognitive

processes cultivated by attentional practices.

Not excluding that for inhibitory control to take place you must not be

fused with what you are experiencing.

Which again is cultivated by attentional meditation practices. This feeds into the next skill - Cognitive flexibility. To be able to perceive another’s

perspective. You would need to go a step

beyond your experiences and to look outside the box of how you would normally react

to a situation. This requires a degree of cognitive flexibility and the

redirecting of our attention from ourselves to someone else. The redirection of attention is a core

cognitive process of attentional meditation practices. Here again, we see accentuated the connection

between attentional and constructive meditation practices and how constructive

practices build on the cognitive processes within attentional practices.

Finally, Perspective taking is more of a social-emotional-intellectual skill, and it still requires us to first utilize our empathic skills to first understand another’s situation.

What does research say: Cognitive reappraisal?

Researchers consider cognitive reappraisal to be an important emotional regulation strategy which when dysregulated can negatively affect our wellbeing. fMRI studies have shown us that cognitive reappraisal activates our brain regions related to cognitive control, these include the dorsomedial, dorsolateral, and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, and the posterior parietal cortex (Buhle, et al., 2014).

For example, a study looking at the effects of cognitive reappraisal with persons affected by social anxiety disorder (Goldin, Manber-Ball, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2009). Found that the effective use of reappraisal as a cognitive process reduced negative thinking in both persons with social anxiety disorder and “healthy controls”. What was of interest was that in “healthy controls” a different pattern of regulatory brain activity was observed. Which pattern was linked to reduced activity in the amygdala when compared to persons with social anxiety disorder.

This decreased activity would mean that an individual can take a more positive active approach when faced by emotional stimuli.

Why? Because if you have a decrease of activity in the amygdala and stronger activity in the prefrontal cortex, the boss in our brain. It means that to a certain degree you can exercise a higher degree of control on what you are feeling.

How the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex communicate

Does this affect our default brain setting?

Returning to the default mode network we mentioned in Part one on attentional practices. Constructive practices (specifically loving-Kindness meditation) also reduced activity in the regions of the brain’s default mode network related to mind wandering (Brewer, et al., 2011).

Furthermore, researchers also saw that loving-kindness meditation reduced activity in the amygdala in conjunction with the reductions in the default mode network (Brewer, et al., 2011). Here again, we can see a clear connection between attentional and constructive meditation practices. More specifically how constructive practices build on the cognitive processes within attentional meditation practices even at the neuronal level.

This is quite interesting as it might show that constructive practices reduce general mind wandering but more specifically mind wandering related to reactivity to emotional stimulus.

Compassion meditation and cognitive reappraisal

When it comes to compassion meditation a study by Weng, et al. (Weng, et al., 2013) found that when shown emotional provoking images meditators had an increased connection between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens.

Where the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is commonly associated with processes like cognitive reappraisal. While the nucleus accumbens is linked to positive emotions in compassion practitioners. Both of these brain areas are associated with social cognition and emotional regulation. And this increased connectivity between these brain areas has been linked with improvements in cognitive reappraisal as an emotional regulation strategy (Wager, Davidson, Hughes, & Ochsner, 2008).

What does research say: Perspective taking?

When it comes to perspective taking research on psychopaths (Decety, Chen, Harenski, & Kienl, 2013) and intergroup prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008) shows that it is vital for healthy interpersonal relationships. As both these studies found that perspective-taking is highly diminished in psychopaths and that it plays a central role when it comes to improving intergroup relationships.

When it comes to brain imaging studies using fMRI. Researchers found that perspective-taking uses multiple different brain areas when it comes to imagining oneself experiencing an undesirable situation when compared to imagining someone else (Ruby & Decety, 2004).

What is interesting is that a study on compassion meditation found that when meditators were shown emotionally provocative images this did not only increase the activity of the brain areas associated with cognitive reappraisal (Engen & Singer, 2015). But it also increased activity in brain regions associated with perspective taking like the supplementary motor area and the posterior cingulate cortex (Ruby & Decety, 2001).

How does this all come together: A constructive process

If the core cognitive processes at work in constructive meditation practices are cognitive reappraisal and perspective taking (Dahl, Lutz, & Davidson, 2015). It could be that these processes are directly targeting negative or neutral thought patterns and replacing them with more positive and assertive thought patterns.

One mechanism through which this could work is the direct transformation of empathy into compassion (Gilbert & Choden, 2014).

Transformation of empathy into compassion

For example, imagine you are on an aeroplane on a long 12 hours flight. Suddenly halfway through the flight shattering the silence you hear a piercing sound. That of a crying baby. Initially, your first reaction to the sound might be a feeling of distress and aversion, wanting the sound to stop counting the seconds as they pass.

Through the processes of cognitive reappraisal and perspective taking, this experience can be totally transformed. By visiting your initial reaction and empathising with the mother putting yourself in her shoes. You might realise that the mother’s initial reaction might also be that of distressed and aversion.

Furthermore, when viewing the situation from the mother’s point of view. Taking the situation from her perspective you might realise how stressful this situation might be for the baby’s mother. She is in a plane full of people with a crying baby doing whatever possible in such a confined environment, the plane, to try to soothe her baby. While at the same time not wanting to disturb the other passengers.

And having to deal with a cascade of negative thoughts about what the other passengers might be thinking etc.

Taking such a view could thereby trigger a sense of warmth and compassion towards the mother. Moreover, by than reinterpreting (using cognitive reappraisal) the sounds of the crying baby as the perfect opportunity to cultivate kindness and concern. Rather than as a direct obstacle to your own peace and well-being.

What we practice grows stronger

Returning to part one of this 3-part series and the notion of, “what we practise grows stronger”. Practising in such a way systematically cultivating compassion in this manner. In time we might start to respond to such aversive stimuli with a compassionate altruistic concern. That might eventually become automatic.

These changes of positive and assertive habit formation have been the subject of study for some researchers. Finding that they are associated with a direct increase in physical and psychological well-being (Lally & Gardner, 2013).

Furthermore, what researchers found was that although compassion is considered to be an innate quality. Compassion is actually not a static quality but can be systematically cultivated (trained) (Weng, et al., 2013).

Researchers actually found that the systemic cultivation of compassion increased the connection between brain areas associated with social-emotional cognition and regulation (Weng, et al., 2013). This suggests that the systematic cultivation of compassion can increase altruistic behaviour because of the engagement and strengthening of brain systems related to the understanding of other people’s suffering.

Moreover, researchers also found that compassion meditation increased activity in brain areas related to empathic accuracy (Mascaro, Rilling, Negi, & Raison, 2013). This increased activity was also associated with improvements in empathic accuracy and the neurobiology supporting it.

So, what about me?

You might ask how might this benefit you? Taking a purely scientific perspective research indicates that the cultivation of compassion for yourself and others can have a positive impact on our physiological, mental, emotional and interpersonal well-being (Jazaieri, et al., 2013; Klimecki, Leiberg, Ricard, & Singer, 2014; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Seppala, Rossomando, & Doty, 2013).

Or more specifically practising a constructive meditation practice, for example, can reduce your perceived stress (Pace, et al., 2010), a direct overall reduction in negative thinking (Goldin, Manber-Ball, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2009) and improve your relationships with others (Seppala, Rossomando, & Doty, 2013).

Constructive meditation practices: Points to reflect on

If we consider all of the above. Reflect on just the notion of being able to reappraise a situation and taking a kinder compassionate perspective towards yourself and others could have a great impact not only on your well-being. But your life in general and your relationship with others.

So if truly this is so and constructive meditation practices increase you empathic accuracy, altruistic responses and have the potential to increase our positive response to suffering (Mascaro, Rilling, Negi, & Raison, 2013; Weng, et al., 2013).

In a way that we take a more active role in addressing and removing the causes of suffering for yourself and others. Looking at the current state of the world. Just reflect on the possible positive impact this could have not only on your life but also on the life of others.

Or as Lama Yeshe says:

Instead of looking at others, telling yourself your usual story about who people are, visualize every person you see as the Bodhisattva of Compassion, the very embodiment of compassion. Deeply doing this, there’s no way you can feel negative toward them.

— Lama Yeshe, “Visualizations”

All material provided on this website are for general informational purposes only read our disclaimer.

Subscribe to our Substack to receive more reflections on meditation, contemplative practices, and the cultivation of mindfulness, compassion, and well-being.

References

Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y.-Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 108(50), 20254-20259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108

Buhle, J. T., Silvers, J. A., Wager, T. D., Lopez, R., Onyemekwu, C., Kober, H., . . . Ochsner, K. N. (2014). Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: A meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex, 24(11), 2981–2990. doi:10.1093/cercor/bht154

Dahl, C. J., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Reconstruction and deconstructing the self: Cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(9), 515-523. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.001

Decety, J., Chen, C., Harenski, C., & Kienl, K. A. (2013). An fMRI study of affective perspective taking in individuals with psychopathy: Imagining another in pain does not evoke empathy. Frontiers Human Neuroscience, 7, 498. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00489

Eifring, H. (Ed.). (2015). Meditation in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Cultural histories. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Engen, H., & Singer, T. (2015). Compassion-based emotion regulation up-regulates experienced positive affect and associated neural networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(9), 1291–1301. doi:10.1093/scan/nsv008

Galinsky, E. (2010). Mind in the making: The Seven essential life skills every child needs. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Gethin, R. (1998). The foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P., & Choden. (2014). Mindful compassion. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Goldin, P. R., Manber-Ball, T., Werner, K., Heimberg, R., & Gross, J. J. (2009). Neural mechanisms of cognitive reappraisal of negative self-beliefs in social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 66(12), 1091-1099. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.014

Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, T. G., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E. L., Finkelstein, J., Simon-Thomas, E., . . . Goldin, P. R. (2013). Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1113-1126. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9373-z

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 9(6), 873-89. doi:10.1093/scan/nst060

Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review, 7(1), S137-S158. doi:10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

Lamm, C., Batson, D. C., & Decety, J. (2007). The neural substrate of human empathy: Effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(1), 42-58. doi:doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545-552. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

Mascaro, J. S., Rilling, J. K., Negi, L. T., & Raison, C. L. (2013). Compassion meditation enhances empathic accuracy and related neural activity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 48-55. doi:10.1093/scan/nss095

Mingyur, R. Y., & Tworkov, H. (2014). Turning confusion into clarity: A guide to the foundation practices of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications Inc.

Pace, T. W., Negi, L. T., Sivilli, T. I., Issa, M. J., Cole, S. P., Adame, D. D., & Raison, C. L. (2010). Innate immune, neuroendocrine and behavioural responses to psychosocial stress do not predict subsequent compassion meditation practice time. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(2), 310-315. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.008

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta‐analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(6), 922-934. doi:doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504

Ruby, P., & Decety, J. (2001). Effect of subjective perspective taking during simulation of action: A PET investigation of agency. Nature Neuroscience, 4(5), 546-550. doi:10.1038/87510

Ruby, P., & Decety, J. (2004). How would you feel versus how do you think she would feel? A neuroimaging study of perspective-taking with social emotions. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(6), 988-999.

Seppala, E., Rossomando, T., & Doty, J. R. (2013). Social connection and compassion: Important predictors of health and well-being. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 80(2), 411-430.

Taylor, S. E. (2017). Health Psychology (10th ed.). London: McGraw-Hill Education Europe.

Wager, T. D., Davidson, M. L., Hughes, B. L., & Ochsner, K. N. (2008). Prefrontal-subcortical pathways mediating successful emotion regulation. Neuron, 59(6), 1037-1050. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.006

Webb, T. L., Miles, E., & Sheeran, P. (2012). Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 775–808. doi:10.1037/a0027600

Weng, H. Y., Fox, S, A., Shackman, A. J., Stodala, D. R., Caldwell, J. Z., . . . Davidson, R. J. (2013). Compassion training alters altruism and neural responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 27(7), 1171-1180. doi:10.1177/0956797612469537