In the first and second article of this three-part series, we looked at what might be the cognitive processes at work in attentional and constructive meditation practices. We saw that attentional meditation practices help us cultivate a degree of emotional regulation. With constructive meditation practices using the cultivated emotional regulation to build onto and change our perception of situations, we encounter from a negative judgmental one to a more neutral, equanimous assertive and compassionate view. Naturally following, we will now be looking at deconstructive meditation practices and the cognitive processes at work here.

Deconstructive Meditation practices

As the name implies, deconstructive Meditation practices take a totally different approach when compared to attentional and constructive meditation practices. How?

In deconstructive meditation practices, you directly inquire and look into the dynamics of your maladaptive thought patterns by exploring any prominent recurrent perceptions and repeating reactive recurring emotional and thought patterns to generate insights into your internal models of self, others and the world (Dahl, et al., 2015).

Our sense of self is a very compelling aspect of our character. It is defined by how you weave together various elements of your life experiences into a coherent yet dynamic everchanging narrative that unifies and gives a sense of meaning to the whole of our lived experience.

Inquiring into this dynamic nature of self is not something new. It is an ancient contemplative practise, practised within a variety of philosophical, religious and contemplative traditions (Hadot, 2016; Harvey, 1995).

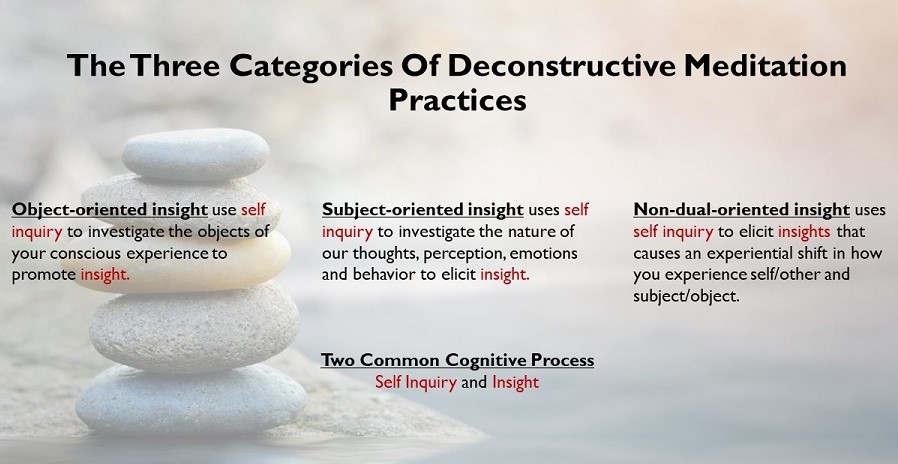

Three categories of deconstructive meditation practices

Like constructive meditation practice, deconstructive meditation practices include within a large variety of meditation practices that try to inquire into the nature of self and experience. Dahl et al. (2015) subdivided the deconstructive family of meditation practices into three categories:

- Object-oriented insight are practices that use inquiry to investigate the objects of your conscious experience (Olendzki, 2011). For example, examining the nature of your physical sensations and observing how they continuously change.

- Subject-oriented insight investigates the nature of our thoughts, perception, emotions and other cognitive and affective processes (Karr, 2007). For example, by examining the subject of your thoughts and feelings dissecting them into their component parts.

- Non-dual-oriented insight take a different approach they aim to cause an experiential shift in how you experience self/other and subject/object (Dunne, 2011). These practices place an emphasis on releasing attempts to try to control, direct, or alter the mind in any way. They also look into dissolving the aspect that the “witnessing observer” is separate from the objects within your awareness.

Furthermore, although these are three distinct families of deconstructive meditation practices, when it comes to sitting down and meditating there are times were one family overlaps the other. For example, you might be doing insight meditation, and at one moment you be using object-oriented insight observing a physical sensation, thereafter going into subject-oriented insight looking into the dynamics of an emotion related to the physical sensations.

From personal experience, I find that insight practice is more of a continuum starting with object-oriented insight and as your meditation practice matures you move into subject-oriented insight and finally non-dual-oriented insight. Although as I commented above during formal meditation practice, none of them is mutually exclusive

Attentional stability a common ground

What is also interesting is that like attentional meditation practices, deconstructive meditation practices also work at maintaining awareness of what you are experiencing. The difference is that deconstructive meditation practice uses the attentional stability cultivated by attentional meditation to plunge into the dynamics of conscious experience (Olendzki, 2011; Shankman, 2015). This is done to try to gain direct experiential insight into the “objects of consciousness”.

Cognitive processes: Self inquiry and insight

Although there is a variety of styles of deconstructive meditation practices, they all aim at unpacking the contents of maladaptive emotional and thought patterns. To do this Dahl et al. (2015) argue that deconstructive meditation practices use the following two core cognitive processes:

- Self inquiry, “the process of investigating the dynamics and nature of conscious experience” (Dahl, et al., 2015, p. 519). This investigation then leads to the other cognitive process.

- Insight, “any sudden comprehension, realisation, or problem-solution that involves a reorganisation of the elements of a person’s mental representation of a stimulus, situation, or event to yield a nonobvious or nondominant interpretation” (Kounios & Beeman, 2014, p. 74). Or what many of us simply call an “aha” moment.

Self inquiry

If you search for self inquiry on google scholar, you will notice that there is a lack of research from the scientific community on what self inquiry is, the dynamics involved and if it leads to any benefits.

Although as to date (Sep12th 2019) self inquiry has not received much attention from the scientific community. As one of their central tenant’s contemplative traditions have for centuries been using a variety of self inquiry techniques to explore the nature of self and experience (Hadot, 2016; Karr, 2007; Maharshi, 2015).

What is also worth mentioning is that a refined form of self inquiry called introspection was developed and used by Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920), the father of psychology, as a form of research technique known as “experimental self-observation” (Henley & Hergenhahn, 2013).

Self inquiry is a complex introspective technique

Self inquiry as an introspective technique is not as straight forward as you may think. At times it might require an unbiased observation of the emotions, thoughts and feelings, that are arising in consciousness; while at the same time noticing how they are continually changing.

Here we can see a link between attentional meditation practices and deconstructive meditation practices. In what way you might ask? Because you need to be able to regulate your attention not to be cognitively fused with what you are experiencing, to successfully use meta-awareness to objectively observe how your thoughts, feelings and emotions are arising and falling in consciousness.

If you look at part one of this 3-part series, you would see that attentional regulation, meta-awareness and reduced cognitive fusion are elements cultivated through attentional meditation practices.

An example of introspection at work

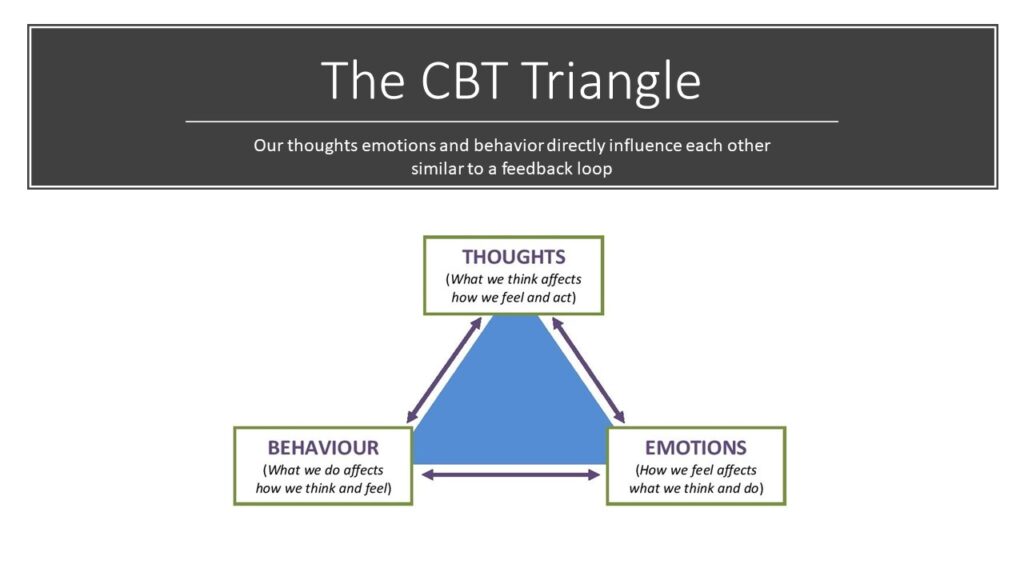

For instance, in this form of self inquiry, if you notice a feeling of anxiety arising, you turn the spotlight of attention towards its component parts. Were you observe how the feeling of anxiety gives rise to anxious thoughts and noticing the physical sensations accompanying such thoughts and feelings. Noticing also how they are constantly changing and affecting each other.

This is similar to the CBT triangle used in cognitive behavioural therapy.

Self inquiry as discursive analysis

Another technique of self inquiry is to use discursive analysis.

In deconstructive meditation practices, this might entail unbiasedly observing the assumptions and underlying reifications relating to a particular object or experience within our field of consciousness. Thereafter objectively questioning the logical consistency of the assumptions and underlying reifications. For example, if you are anxious, you might identify the fearful assumptions that underlie the emotion and then inquire into the rational basis for your beliefs.

This is an active form of insight which requires a high degree of concentration and emotional regulation (Shankman, 2015).

Again, we can see a link between attentional and constructive meditation practices. As, as mentioned in part one of this 3-part series, attentional meditation practices cultivate emotional and attention regulation.

Furthermore, in deconstructive meditation practice, self inquiry and discursive analysis techniques, are also used to examine beliefs about the self, the nature and dynamics of perception, the unfolding of thoughts and emotions, and the nature of awareness and reality itself (Hadot, 2016; Harvey, 1995; Maharshi, 1991).

So, in deconstructive meditation practices, self inquiry is purposefully used to elicit the arising of insight.

From self inquiry to insight

Unfortunately, to date (Sep13th 2019), a google scholar search seamed to reveal that the scientific community, has not given much attention to the scientific study of insight, arising through self inquiry. As we discussed above, this also seems to be the case with self inquiry.

The issue here could be that because self inquiry is quite an abstract, subjective to the individual and broad concept. Therefore, it would be quite challenging to operationalise self inquiry into a definite universal construct, which could be then used for research. Consequentially, as we have seen, this would reflect in a lack of research on the correlates of insight from self inquiry.

Although challenging, this could be an interesting subject for future research. Especially considering that several contemplative traditions hold that insight elicited through self inquiry, specifically inquiring into the nature of “self” might be of importance to the cultivation of well-being (Hadot, 2016; Maharshi, 1991; Harvey, 1995).

What about Insight

Insight can be compared to a sudden shift in consciousness, accompanied by a bodily and mental feeling of knowing or having an understanding of perceiving the meaning of “something” that previously escaped your grasp.

The scientific study of insight has mainly focused on the sudden burst of understanding you might feel after solving some semantic, visual or mathematic problem or when you abruptly gain a solution to a problem and the differences between “aha!” and non-aha!” experiences (Bowden & Jung-Beeman, 2003; Danek & Flanagin, 2019; Ishikawa, et al., 2019a; Ishikawa, et al., 2019b).

Research on meditation and insight

There have also been some studies looking at the effects of mindfulness meditation practice and mindfulness vipassana meditation practice and insight. For example:

A study done by Surinrut et al. (2016) on the effects of a mindfulness vipassana seven-day meditation retreat found, that this form of mindfulness insight practice was associated with enhanced feelings of happiness and a general reduction in feelings of negative functioning, such as perceived stress.

Similarly, Nakajima et al. (2019) argued that a degree of mindfulness can be a prerequisite to gaining self-insight. They suggested this as their findings indicated that mindfulness practice could enhance self-insight. Not only, they also noticed that these improvements in self-insight through mindfulness were linked to a reduction in depressive symptoms in Japanese undergraduate students.

Another study on the effects of short-term mindfulness practice on brain activity related to insight found that compared to the control group, after a short-term five-hour mindfulness training the meditation group showed increased activation in the following brain areas: right cingulate gyrus, bilateral middle frontal gyrus, right inferior frontal gyrus, right insula, bilateral inferior parietal lobule and superior temporal gyrus and the right putamen (Ding, et al., 2015).

All these brain areas have been linked to insight-associated cognitive processes (Kounious, et al., 2008). Including the highly integrated processes such as conflict detection, breaking mental set, restructuring problem representation, error detection and the “Aha!” experience (Kounios & Beeman, 2014).

Again, in the above studies, we see insinuated a link between attentional meditation practices and deconstructive meditation practices. Mainly how mindfulness, a quality cultivated through attentional meditation practices, might be a foundational element for the arising of insight, particularly when it comes to deconstructive meditation practices.

A Link between attentional and deconstructive meditation practices

The above-mentioned studies seem to suggest that attentional meditation practices can also lead to the arising of momentary insights.

Although it is known that a well-cultivated mindfulness leads to experiencing momentary insights (Shankman, 2015). The arising of insight is not considered as a central cognitive process in attentional meditation practices. So, what is the connection between the insight that arises during attentional and deconstructive meditation practices?

Insights arising from the strengthening of cognitive processes cultivated in attentional meditation practices are usually quite momentary. The connection lies here, that in deconstructive meditation practices insights that are typically considered momentary and fleeting are systematically stabilised and integrated into your lived experience.

Such that although distinct, the cognitive processes at work within both attentional and deconstructive meditation practices are considered necessary for the arising of insight (Gethin, 1998; Hadot, 2016; Shankman, 2015).

Why? Because the cognitive processes of meta-awareness and reduced experiential fusion cultivated in attention meditation practices are the light of mindfulness that shines so that insight arises. Then through the self inquiry carried out in deconstructive meditation practices, these insights are stabilised and further explored. Let us consider the following example:

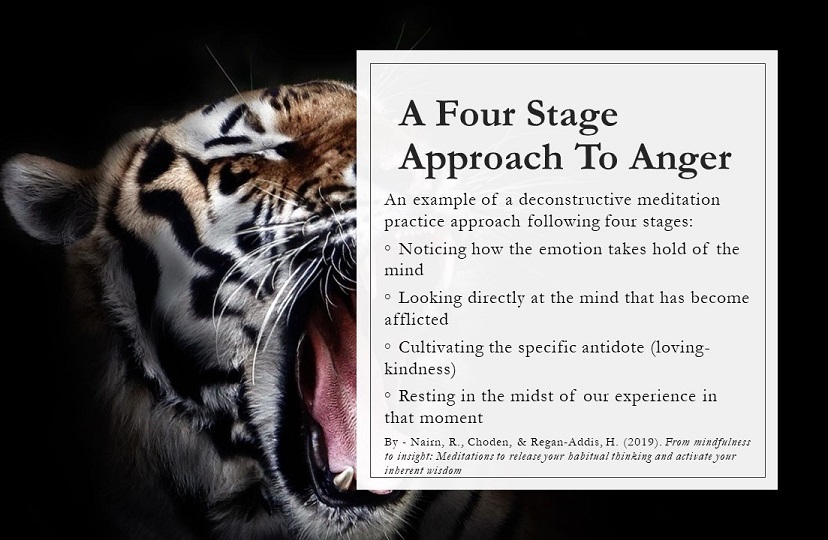

Being overcome by anger: attentional and deconstructive processes at work

Consider a situation where you felt overcome by anger (or any other emotion). When you become overwhelmed by the feeling of anger, your sense of self becomes fused with anger. It no longer remains a feeling of anger; you become anger, as if your whole being is an expression of anger; it’s like you are going to burst.

You no longer see that the anger is an emotion that arose within you, but instead “I am angry – I am anger”. Because of this you start perceiving what you are experiencing through the lens of anger. As if suddenly you put Infront of your eyes glasses which have lenses made from anger and this colours your whole experience with anger.

If attentional meditation practices train our emotional regulation capacity, so you become less fused with what you are experiencing and more meta-aware of your thoughts and feelings. This would help you better recognise the occurrence of different emotional mind states.

In our example a state of anger, enabling us to notice the presence of angry thoughts and the physiological changes accompanying the anger, as occurrences within you. This kind of sustained recognition allows you to objectively see and investigate this experience of anger. Such an approach is used by deconstructive meditation practices (Goldstein, 2003; Nairn, et al., 2019; Shankman, 2015).

Conclusion

Summarising the above deconstructive meditation practices take this sustained awareness (meta-awareness) to also investigate the various components within the experience of anger, for example by:

- Inquiring into the nature of anger and how it relates to your sense of self both physically and mentally.

- Uncovering any implicit beliefs that trigger the arising of anger

- Then questioning the nature of these beliefs in relation to your present moment experience

Investigating conscious experience in such a way is said to elicit insight (Nairn, et al., 2019; Shankman, 2015). Or experiencing a sudden flash of intuitive understanding which can then be stabilised with the help of meta-awareness.

Thus, meta-awareness cultivated in attentional meditation practices sets the stage for the cognitive process of self inquiry within deconstructive meditation practices. Such that when meta-awareness is coupled with self inquiry, it allows for the stabilisation of the insight’s generated. While at the same time being two totally distinct cognitive processes which are both necessary for the arising and stabilisation of insight’s in meditation.

Final note

Coming to the end of this 3-part series on the cognitive processes in attentional, constructive and deconstructive meditation practices. I would end by commenting that although these practices are usually presented as separate from each other. As we saw through this series they also seem to be connected. Most prominently attentional meditation practice to constructive and deconstructive meditation practices.

As it seems that the emotional regulation, meta-awareness and decentering cultivated in attentional practices are needed as a base for the successful practice of constructive and deconstructive meditation practices.

This leaves us with the following question. What if the cultivation of mindfulness is the starting point for all these practices? What do you think? Leave us a comment below.

References

Bowden, E. M., & Jung-Beeman, M. (2003). Aha! Insight experience correlates with solution activation in the right hemisphere. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10(3), 730-737.

Dahl, C. J., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Reconstruction and deconstructing the self: Cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(9), 515-523. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.001

Danek, A. H., & Flanagin, V. L. (2019). Cognitive conflict and restructuring: The neural basis of two core components of insight. AIMS Neuroscience, 6(2), 60–84. doi:10.3934/Neuroscience.2019.2.60

Ding, X., Tang, Y.-Y., Cao, C., Deng, Y., Wang, Y., Xin, X., & Posner, M. I. (2015). Short-term meditation modulates brain activity of insight evoked with solution cue. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(1), 43-49. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu032

Dunne, J. (2011). Toward an understanding of non-dual mindfulness. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 71-88. doi:10.1080/14639947.2011.564820

Gethin, R. (1998). The foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldstein, J. (2003). Insight meditation: The practice of freedom. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications Inc.

Hadot, P. (2016). Philosophy as a Way Of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault. (A. Davidson, Ed., & M. Chase, Trans.) Oxford: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Harvey, P. (1995). The selfless mind: Personality, consciousness and nirvana in early Buddhism. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Henley, T., & Hergenhahn, B. R. (2013). An Introduction to the History of Psychology (7 ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc.

Ishikawa, T., Toshima, M., & Mogi, K. (2019a). How and When? Metacognition and solution timing characterize an “aha” experience of object recognition in hidden figures. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1023. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01023

Ishikawa, T., Toshima, M., & Mogi, K. (2019b). Phenomenology of Visual One-Shot Learning: Affective and Cognitive Components of Insight in Morphed Gradual Change Hidden Figures. In H. Lu, H. Tang, & Z. Wang (Eds.), Advances in Neural Networks – ISNN 2019 (pp. 522-530). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22808-8_51

Karr, A. (2007). Contemplating reality: A practitioner’s guide to the view in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications Inc.

Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2014). The cognitive neuroscience of insight. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 71-93. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115154

Kounious, J., Fleck, J. I., Green, D. L., Payne, L., Stevenson, J. L., Bowden, E. M., & Jung-Beeman, M. (2008). The origins of insight in resting-state brain activity. Neuropsychologia, 46, 281-291. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.013

Maharshi, R. (1991). Be as you are the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi (Reissue ed.). (D. Godman, Ed.) London: Penguin Random House India.

Maharshi, R. (2015). The yoga of self inquiry [epub]. San Diego, CA: Ramaji Books.

Nairn, R., Choden, & Regan-Addis, H. (2019). From mindfulness to insight: Meditations to release your habitual thinking and activate your inherent wisdom [epub]. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Nakajima, M., Takano, K., & Tanno, Y. (2019). Mindfulness relates to decreased depressive symptoms via enhancement of self-Insight. Mindfulness, 10(5), 894–902. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-1049-2

Olendzki, A. (2011). The construction of mindfulness. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 55-70. doi:10.1080/14639947.2011.564817

Shankman, R. (2015). The art and skill of Buddhist meditation mindfulness, concentration, and insight. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Surinrut, P., Auamnoy, T., & Sangwatanaroj. (2016). Enhanced happiness and stress alleviation upon insight meditation retreat mindfulness a part of traditional Buddhist meditation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture,19(7), 648-659. doi:10.1080/13674676.2016.1207618

The example of anger is particularly relevant to me, I must say. I try to be calm and patient as much as possible, and people actually tell me that and even tell me that they don’t imagine me “losing it”, but like everyone, I have my limits. I tend to be the kind of person that bottles up and then explodes, and that is not good.

An other thing which I notice that I do is avoid conflict as much as possible… to the point where I am not assertive, though. I hate arguments and fighting even more. Sometimes we need to speak up, otherwise people will walk all over us.

If I may add my own opinion, some of us that feel like this need to examine their past and see if there were instances which affected their self-esteem, and move on from there. This is just my opinion, of course. Thank you for the post, my friend.

quite a good point about how past experiences affect us

Thank you, your clarity is greatly appreciated!

🙂