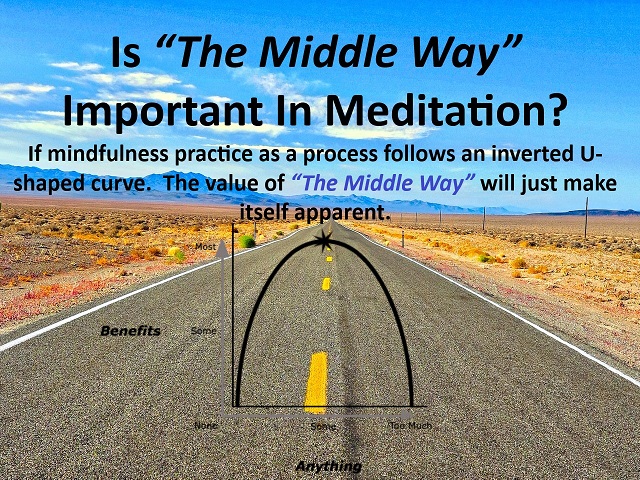

Why is “The Middle Way” important in meditation? In a recent blog post, we looked at the possibility that mindfulness practice follows an inverted U-shaped curve. This means that there could be an “optimal” point of meditation practice after which, the resulting mindfulness-related processes can turn “sour”. This could actually be seen as a reflection of the argument made in the philosophical teaching of meditation related to the value of “the middle way” (Dalai Lama, 2009).

In his research article Britton (2019) argues for “the value the middle way” in meditation practice. He argues that mindfulness-related processes resulting from the practice of meditation are usually beneficial. On the flip side he also argues that, “under certain conditions, for certain people, or at certain levels, their effects can turn negative, have costs, or have undesirable effects” (Britton, 2019, p. 161). Still, this is not as straight forward as it sounds as there are multiple mindfulness related processes, namely: mindful attention (mind-body awareness, interoception), mindfulness qualities, mindful emotion regulation (prefrontal control, decentering, exposure, acceptance), and mindfulness meditation practice. These could result in both positive and negative effects. Although Britton argues that there are other factors that could influence such effects. Following are some moderating factors.

Dose or practice amount

When it comes to dose, if we return to the inverted U-shaped-curve principle. It argues that the same underlying mechanisms that cause beneficial effects. Are also responsible for the adverse effects caused by the too-much-of-a-good-thing model. Putting it simply this model argues that negative effects from meditation could also result even if one follows correct procedural practices. Not excluding that as practice length or frequency increases such negative effects could be more likely. However, Britton argues that such inflexion points could be influenced by the following factors.

Practitioner characteristics

The inverted U-shaped-curve non-monotonicity model would also indicate that participants with certain characteristics are more likely to experience positive or negative effects respectively. The model would predict that people with low levels of mindfulness-related processes will experience more positive effects. While people with high levels of mindfulness-related processes would be more likely to experience negative effects.

For example, if we take the mindfulness-related processes of self-observation. Individuals with a low level of self-awareness are more likely to improve their self-awareness. Therefore, the increased possibility of experiencing positive effects. Still this up to a point. On the other had individuals with high levels of self-focus, especially individuals lacking other mindfulness skills are more likely to experience negative effects. For example;

A study by Sahdra et al. (2017) examining mindfulness skills profile found that individuals with high levels of self-focus were more likely to experience psychological difficulties. Although the researchers also found that such group experience the highest levels of life satisfaction. This could point out that meditation practice is like a balancing act between different mindfulness-related processes.

The Middle Way: A balanced practice

So, if high levels of mindfulness-related processes can cause negative effects. Can other mindfulness related processes act as a counterbalance? The research conducted by Sahdra et al. (2017) actually suggests this. That when high levels of “self-awareness” become counter-intuitive. They can be balanced with the mindful skill of “non-judgment”. Putting it simply, if a person becomes highly self-aware to the extent that they start to experience critical self-defeating thoughts and feelings. This could be balanced with the appropriate application of the mindfulness skill of non-judgment.

Person-by-context interaction

Looking at the interaction between the above factors in conjunction with the argument made in a previous blog post. Meditation practice as a process is not as straightforward as one would like to think. In fact, meditation practice as a process can be likened to a balancing act between different mindfulness related processes.

It could be argued that in the teaching and practice of meditation what the individual brings with him to the practice is of paramount importance. Or in simpler terms the specific needs of the person are central and what works for one might not work for another. To this Britton (2019) argues that we need to ask, “how much of which mindfulness related processes is optimal for this specific person in this specific situation, according to this person’s goals and values?” (p. 162). With Sahdra et al. (2017) commenting that, “mindfulness cannot be fully understood as ‘more is better, less is worse.’ . . . Rather, it’s how the different mindfulness skills combine in a person that may be most important for his or her mental health” (p. 363).

The value of The Middle Way

Personally, this reminds me of the stance of equanimity and the importance of looking for what has been called “the middle way”. Or an appropriate balance between different mindful skills both in our personal practice and most importantly in our teaching practice. As Sahdra argues it’s the balanced way that we apply and combine appropriate levels of mindfulness skills. Might be the most important skill for ourselves and for others to benefit from meditation as a practice. Not excluding another crucial element, the appropriate application of balanced compassion both for self/others within our practice (Dalai Lama, 2009). Such is the value of “The Middle Way” in meditation.

All material provided on this website are for general informational purposes only read our disclaimer.

Subscribe to our Substack to receive more reflections on meditation, contemplative practices, and the cultivation of mindfulness, compassion, and well-being.

Bibliography

Britton, W. B. (2019). Can mindfulness be too much of a good thing? The value of a middle way. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 159-165. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.011

Dalai Lama. (2009). The middle way: Faith grounded in reason. (T. Jinpa, Trans.) Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Sahdra, B. K., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., Basarkod, G., Bradshaw, E. L., & Baer, R. (2017). Are people mindful in different ways? Disentangling the quantity and quality of mindfulness in latent profiles and exploring their links to mental health and life effectiveness. European Journal of Personality, 31(4), 347–365. doi:10.1002/per.2108