Meditation and mindfulness practices have been a subject of research for both cognitive and neuroscientists. In recent years research in such area has gained traction towards trying to understand the possible cognitive processes involved in meditation practices. This to attempt to classify them into a basic taxonomy according to the cognitive processes in common between popular practiced forms of mindfulness meditation (Nash & Newberg, 2013).

Expanding on their previous research (Lutz, et al., 2008). Dahl et al. (2015) propose a framework which groups meditation and mindfulness practices according to the primary cognitive processes common to each practice. They proposed three categories with the corresponding cognitive processes:

- Attentional practices which cultivate the cognitive processes of attention regulation and meta-awareness.

- Constructive meditation practices which cultivate the cognitive processes of perspective-taking and reappraisal

- Deconstructive meditation practices which cultivate the cognitive processes of self-inquiry.

This is the first of three blog post where we will look at these three proposed meditation categories. The possible corresponding cognitive processes at work, their effects and possible benefits.

Attentional meditation practices

As the name implies mindfulness attentional practices are focused towards training the processes involved in the regulation of attention. This includes the ability to monitor, detect and disengage from distractors by redirecting your attention towards a chosen object of focus (Lutz, et al., 2015). Dahl et al. (2015) comments that shared characteristics of mindfulness attentional practices is; “the systematic training of the capacity to intentionally initiate, direct, and/or sustain these attentional processes while strengthening the capacity to be aware of the processes of thinking, feeling, and perceiving” (p. 516).

Cognitive processes: Meta-awareness and experiential fusion

This has been called meta-awareness or the innate ability to be aware of the process of thinking. Without such awareness, we can easily end up fused with the contents of our experience (Smallwood, et al., 2007). That means that we might be aware of the object within our attention but blind to the thoughts perceptions and feelings going on behind the object. This might sound counter-intuitive and you might ask. How can I be aware of an object yet blind to the process of consciousness behind it?

A good example to illustrate this is the analogy of watching a movie. Imagine you are at the movie theatre. You might experience moments where you are so captivated by the movie. That for a moment you might lose awareness of your surroundings and that you’re sitting watching a movie (experiential fusion) and find yourself “screaming”. The next moment your friend might tap your shoulder and suddenly you become aware of your surroundings and that you are sitting watching projected images on a screen.

In both instances, you were attentive to the movie and you would easily tell someone what was happening in the movie. Yet if you were to ask yourself if you were also aware that you were sitting watching a movie before you were tapped on the shoulder. The answer might be no. So only in the second instance where you both aware of the movie and the “process of watching it”. This could be likened to meta-awareness.

What does research say on meditation attentional practices

Difficulties with attention regulation and Experiential fusion has been linked to substance addiction, psychological disorders and differences in brain function and structure (Bockstaele, et al., 2014; Brewer, et al., 2014; Hoge, et al., 2015; Waters, et al., 2012).

For example, a study found that persons undergoing therapy for depression particularly mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reported decreases in processes related to experiential fusion (Bieling, et al., 2012). Persons undergoing a smoking cessation program including mindfulness practice also reported that mindfulness practice altered the relationship between their craving and behaviour of smoking (Elwafi, et al., 2013).

Brain imaging studies have also found possible structural changes in the brain and a strengthening of the brains attentional networks (Fox, et al., 2014). Furthermore, electroencephalogram (EEG) studies are finding that mindfulness practice helps with one’s attentional stability especially on continues performance tasks (Lutz, et al., 2009).

But how does this work?

It’s thought that mindfulness practice increases attentional stability which in turn reduces experiential fusion by cultivating meta-awareness. Or the ability to regulate attention helps us to take a step back and observe one’s process of thinking. This, in turn, should facilitate emotional regulation especially by decreasing the preservation of negative emotional thoughts (Marchand, 2014).

For example, if a particular situation or incident causes a feeling of anxiety. The ability to regulate attention and not be at the mercy of our thoughts wondering on every possible negative outcome. Creates a virtual space between our thoughts and the situation. We become less fused with our experience. This virtual distance helps in seeing through meta-awareness that the feelings of anxiety within me are a consequence of something external.

Having such an understanding of the process of how such feelings of anxiety were evoked. Should reduce the preservation of anxious feelings related to that situation. That is, we no longer keep remunerating on the situation, one does not keep thinking about it.

So how does this impact our wellbeing?

For example, a seminal study by Killingsworth and Gilbert (2010) found that we pass as much as 50% of our lives in mind wandering. This can have a profound impact on our general sense of well-being. The author’s comment, “a human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind. The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost” (p. 932).

If this is the case and if attentional meditation practices cultivate meta-awareness this, in turn, should reduce mind wandering and increase wellbeing. Research seems to indicate that this is the case and a study conducted by Mrazek et al. (2012) found that mindfulness attentional training reduced thoughts unrelated to the task one is doing. With a corresponding decrease in the behavioural markers of mind wandering. Furthermore, a recent study by Rahl et al. (2017) found that a brief 3-day mindfulness attentional training with acceptance also reduced thoughts unrelated to the task one is doing together with a decrease in the behavioural markers of mind wandering.

A default mode setting

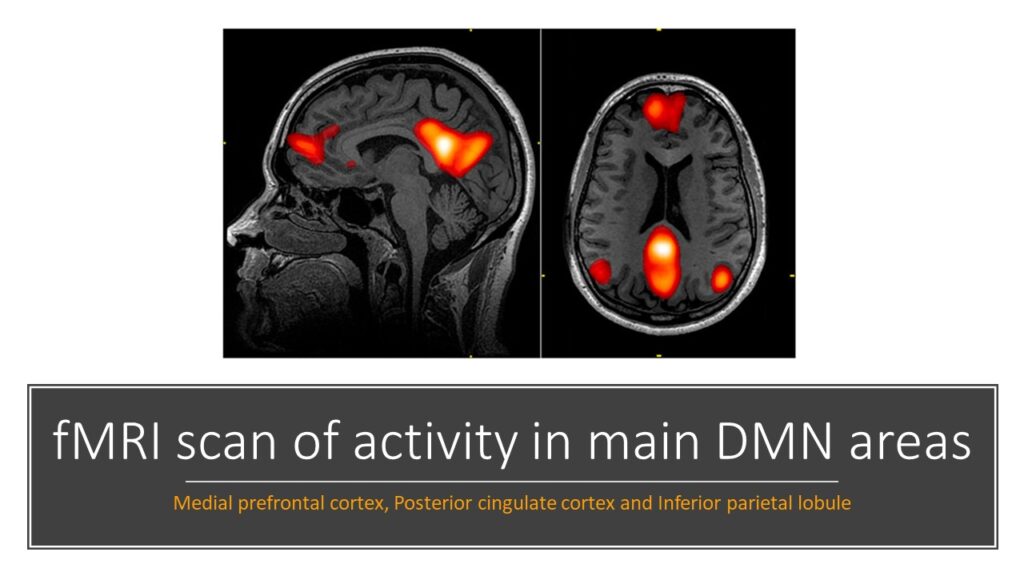

What is of interest is that brain imaging indicates that by default parts of our brain are wired together in a way that promotes mind-wandering and self-referential thinking (Gusnard, et al., 2001). This network of brain areas has been called the default mode network (DMN) (Raichle, 2015). What researchers found was that during attentional meditation practices the default mode network got less activated especially the areas related to self-referential thinking (Xu, et al., 2014). Research also indicates that in people who regularly practice meditation these effects persisted after the meditation practice and were carried on into daily life (Taylor, et al., 2012).

Brain plasticity

If truly our brain is plastic this could have a profound effect in relation to our wellbeing. This caused a spark of interest. In fact, research indicates that as a consequence of meditation certain areas of the default mode network were getting less activated (Brewer, et al., 2011). In time researchers observed that this resulted in the weakening of connectivity in the DMN areas related to self-referential processing and a reduction in mind wandering. Unbecomingly what was of most interest was that this weakening resulted in increased connectivity between other particular regions of DMN which enhanced present moment awareness (Taylor, et al., 2012).

So, where does this leave us

I think that understanding the possible cognitive process in attentional meditation practices can be quite helpful. This not only in relation to being able to create some form of a classification system.

But having an understanding of the underlying cognitive processes in attentional meditation practices can be of profound significance in other areas. Especially if attentional practices work through the cognitive process of attention regulation, meta-awareness and cognitive fusion. This because the regulation of attention, meta-awareness and reduced cognitive fusion have been found to be factors which aid in one’s recovery from mental health issues and substance addiction (Bieling, et al., 2012; Brewer, et al., 2014; Hoge, et al., 2015).

As attentional meditation practices foster the cultivation of such cognitive processes. Understanding the mechanisms involved. Can further our understanding of the application of which attentional meditation practice would be most helpful in a given therapeutic situation. Possibly aiding recovery, reducing relapse rate and enhancing therapy outcomes.

But what about the average individual – “Me”

Well if it is true as research points out that we spend 50% of our time mind wandering, and that our brains are by default wired in a way to promote self-referential thoughts and worry. Especially when you are at rest. It might be argued that we might be a hostage to our own neurobiology.

Evolutionary this might be true. Still, I beg to differ as neuroscience has also shown that our brain has a great propensity to rewire itself. One of the fundamental mantras in neurobiology is Hebb’s law “neurons that fire together wire together”. Or as Dr Shauna Shapiro says, “what you practice grows stronger” (see video).

So, if you practice being angry our neuronal angry pathways in our brain get stronger. Similarly, if you practice being worried those pathways in the brain will get stronger. What if you practice an attentional meditation practice which cultivates emotional regulation, meta-awareness and less cognitive fusion?

Considering the above reasoning of “what you practice grows stronger”. Then with regular meditation practice, our minds would wander less and we would be more present. And precisely this is what neuroscientists are finding. That practising meditation has a propensity to remold the default wiring (Default mode network) of our brains possibly reducing self-referential thinking and enhancing present moment awareness.

Putting it simply and from personal experience with meditation practice your mind will still wander and you would still have worries. But unbecomingly you feel less troubled by them and more focused on the present with what you’re doing. This has been found to promote a general sense of well-being. Isn’t this something we all want?

Any thoughts comment below and subscribe to stay tuned for our next post on Constructive meditation practices which cultivate the cognitive processes of perspective-taking and reappraisal.